Why the High Seas Treaty is critical to the success of 30×30 in the ocean

The High Seas – the entire ocean, seafloor and water column outside national jurisdictions – was for many years widely perceived as a lawless wilderness. And there are good reasons why. Since Hugo Grotius, one of history’s most famous legal scholars, established the “freedom of the seas” doctrine in 1609, these vast ocean areas have essentially belonged to no one, meaning everyone could freely fish, ship and conduct research in them.

With a growing human population and advances in technology enabling us to exploit further, faster and deeper into these waters, the need to better manage the ocean has intensified. Although the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea was adopted in 1982, provisions to govern the High Seas and protect biodiversity remained patchy, leaving critically threatened ecosystems and the incredible diversity of life they support vulnerable to increasing pressures.

This really matters because we cannot effectively restore nature, stabilize the climate, and secure a healthy future for everyone unless we safeguard our international waters.

WHAT IS THE HIGH SEAS?

Covering half of our planet and two-thirds of the global ocean, the High Seas is the largest habitat on Earth. It sustain and connects all life by powering the water cycle and regulating the weather. It supplies us with almost half the oxygen we breathe. And it curbs some of the most catastrophic impacts of climate change by absorbing more than 90% of our excess heat and over a quarter of our carbon-dioxide emissions, while providing a valuable source of protein for billions of people.

Even though it is our life support system, today only 1.5% of the High Seas is effectively protected.

THE HIGH SEAS TREATY AND 30X30

Fortunately, this dire situation is set to improve. June 2023 ushered in an historic opportunity to reduce the harms we inflict on the ocean when UN Member States adopted the Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ), commonly known as the High Seas Treaty. This was a deeply significant achievement at a time when multilateralism faces many challenges.

Once it enters into force, the Treaty will blow wind into the sails of other efforts to restore the health of the ailing ocean. Not only will it give the international community a greater say in decisions regarding new activities that could harm biodiversity beyond borders through its provisions on environmental impact assessments (EIAs), but it will also provide the world’s first legal framework to create area-based management tools (ABMTs) in the High Seas, including marine protected areas (MPAs). Networks of effective MPAs in our international waters are critical to achieving the global commitment to conserve at least 30% of the ocean by 2030 (30×30), agreed by nations in 2022 under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

The Treaty also advances progress by promoting greater equity and participation among nations through capacity building, marine technology transfer, financing, and fair access to and benefit sharing of marine genetic resources (MGRs) and their digital representation (Digital Sequence Information, or DSI). It recognizes the invaluable contributions of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLC) and their traditional knowledge and provides for their inclusion in the decision and policy-making process. It also supports progress by enabling decisions to be made by a majority vote if a consensus cannot be reached.

THE RACE FOR RATIFICATION

Achieving the level of global governance required to restore ocean health not only rests on an unparalleled level of political ambition and action, but – with just six years left to achieve the 30×30 target – on the speed at which nations ratify, operationalize and implement the High Seas Treaty.

All treaties must be signed and ratified by an agreed number of UN Member States before they enter into force and become international law. In the case of the High Seas Treaty, that number is 60. To galvanize action, world leaders are rallying around the race for ratification, with the original ambition of securing at least 60 ratifications by the third UN Ocean Conference (UNOC) in June 2025. When the sixtieth country ratifies, it will trigger a 120-day countdown toward entry into force of the High Seas Treaty.

WHO IS IN THE LEAD?

Within two days of its opening to signatures at the UN on 20 September 2023, as many as 75 Member States signed the High Seas Treaty, thereby expressing their willingness to proceed to ratification. This number has since climbed to 137 signatories. Four months later, Palau became the first country to officially ratify the Treaty at the UN, followed closely by Chile. 50 countries have now ratified (June 2025).

The political ambition to reach 60 ratifications is intensifying, especially among countries that have started their ratification process but did not complete it by June. This is because, while the ratification of a treaty can be as swift as the stroke of a pen by a President in some countries, others require parliamentary and legislative processes that can take many months, or even years, to complete. Elections can also interrupt the process, inserting unwanted delays.

Ultimately, the aim is for universal ratification of the Treaty by all UN Member States. To ensure it is as effective and equitable as possible, it is hoped these will represent a large and diverse range of developed and developing nations, Small Island Developing States (SIDS), large maritime nations, and key international and regional ocean players.

While it involves varying levels of time and work across nations, the heat is on for all world leaders to prioritize early ratification of the High Seas Treaty so that we can win the race against time to achieve 30×30, rebuild the ocean’s health and resilience and mitigate climate breakdown. Keep track of developments on the High Seas Alliance country progress map.

PREPARING FOR ACTION IN THE HIGH SEAS

With the aim of swiftly transforming the High Seas Treaty Agreement into action in the water, the global community has already started preparing for its entry into force and first Conference of Parties (COP). A BBNJ Preparatory Commission (PrepCom) was established in April 2024 and two Prepcom meetings have been scheduled for 2025, on 14-25 April and 18-29 August.

These meetings will set the stage for the Treaty by starting to address its institutional building blocks, such as its committees, funds, systems, rules and procedures, ready to inform decision-making at the first BBNJ COP. It is essential that these building blocks are thoughtfully designed so that the Treaty can function efficiently, effectively and transparently to deliver equitable conservation of the High Seas.

PREPARING THE CASE FOR HIGH SEAS MPAS

At the same time, efforts are also underway by governments and organizations to prepare for putting its provisions into practice, including the first recommendations for a network of High Seas MPAs.

Salas y Gómez and Nazca Ridges

The Salas y Gómez and Nazca Ridges of the South East Pacific have been extensively studied by scientists, and has been recognized as an ecologically and biologically significant area (EBSA), that requires protection and conservation. Chile and Peru have already protected the portions that lie within their national jurisdiction, but 73% lie in the High Seas, where they are currently unprotected.

Protecting the Salas y Gómez and Nazca Ridge as an MPA under the new High Seas Treaty would be a global accomplishment. In 2024, an exploration of 10 seamounts in the region by the Schmidt Ocean Institute discovered more than 100 potential new species, thereby helping to build a scientifically rich baseline to advance the case for protections.

Lord Howe Rise – South Tasman Sea

In October 2024, High Seas Alliance, WWF and the Deep Ocean Stewardship Initiative announced a collaboration with the Australian Government to begin work to develop the case for a protected area in the High Seas of Oceania. A planned science and knowledge symposium in early 2025 will bring together key stakeholders to present and discuss the existing ecological, cultural, and commercial values of the Lord Howe Rise – South Tasman Sea.

Referred to as ‘a volcanic lost world’, this area has been identified by global experts as a priority site for nomination as one of the first High Seas MPAs under the new Treaty due to its extraordinary biological diversity and unique ecological features, many of which have been identified as vulnerable marine ecosystems. The aim is to map these features and begin stakeholder discussions about the area’s future management and protection as an MPA under the High Seas Treaty, once it enters into force.

Read about other proposed High Seas MPAs.

The days of regarding the High Seas as a lawless wilderness are over. Marine life does not recognize boundaries, so it is essential that we secure 30% protection of all seas by 2030, both within and beyond national waters.

I hope you can join us on this restorative journey towards a healthy, thriving ocean for present and future generations. We invite you to add your voice to this global map of messages to inspire world leaders to act now and ratify the High Seas Treaty.

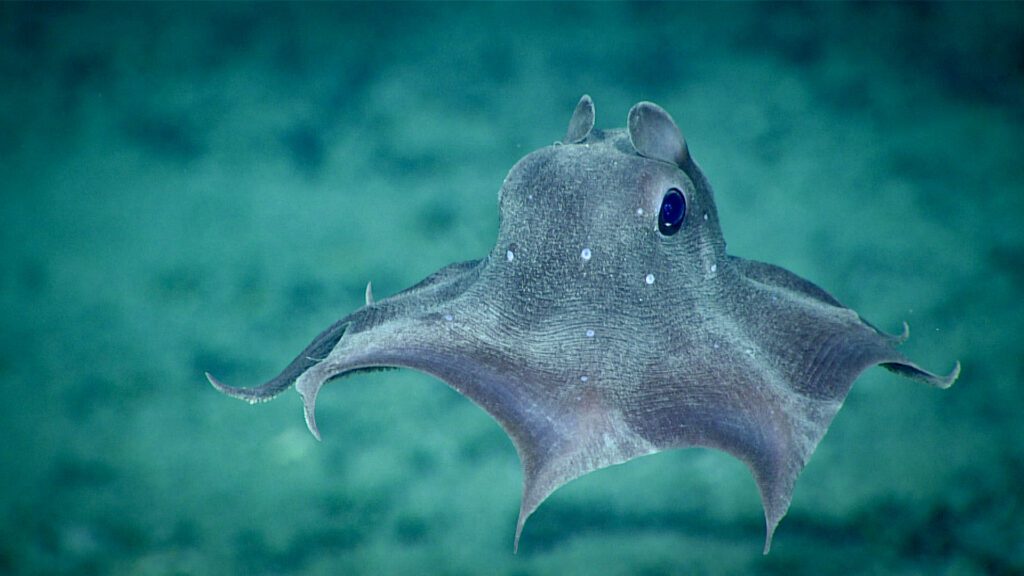

Header image credit: François Baelen Ocean Image Bank

About the author

Born and raised on the south coast of Australia, Rebecca has a degree in Environmental Science, and has spent the last 20 years working on environmental campaigns with NGOs from the local to international level. Creativity, community mobilisation and alliance building have been central pillars to her work on issues ranging from ancient forest protection to sustainable fisheries management.